From Bootstrap to Mantine: 8 Years of UI Evolution

1 September 2025

The Excuse We'd Been Waiting For

January 2024. Our new Chief Creative Officer shares refined brand guidelines on Slack -- subtle updates, mostly: adjusted colors, a new logo, a couple of new fonts. Nothing that would break Aurora, (our design system / component library) outright.

That being said, Aurora was already showing its age. Over three years of components still built on Semantic/Fomantic foundations. Over three years of architectural decisions we'd outgrown. And over three years of this workflow: 1) update components library, 2) create an alpha release, test across 8+ applications, QA, bump to patch or minor release, test across 8+ applications again, QA again, deploy.

Exhausting.

The 2024 rebrand was our opportunity to address what we'd been avoiding: Aurora, built on the increasingly outdated semantic-ui-react library, using a fomantic-ui theme -- was starting to become a bit of a burden, and maybe not as beneficial as it once was.

As part of researching and digging around for this piece, I dove into our git history to understand the scope of what we'd built. Between 2020 and 2021, as we developed the Aurora components library, we'd made over 1500+ commits to kip-ui-packages and a variety of our applications to use these updates -- a period of rapid iteration through alpha releases that told the story of a system being built. With all that very rapid iteration though, comes a maintenance burden that was very real, and everyone who'd touched Aurora knew it.

But to understand how we got here, why we built Aurora in the first place... you need to see the whole journey.

2016-2018: Bootstrap; The Right Choice for Its Time

October 26, 2016. Our first commit.

{

"bootstrap": "^3.3.7",

"react-bootstrap": "^0.30.5",

"react": "^15.3.2",

"react-dom": "^15.3.2"

}In retrospect, Bootstrap 3.3.7 in 2016 was the obvious choice.

It was stable, well-documented, and react-bootstrap provided exactly what we needed for rapid internal application development. For 18 months, this foundation served us well, enabling us to focus on business logic rather than UI architecture.

That being said, here's what that actually looked like in practice. Manual LESS variables defining our color system:

@white: #ffffff;

@dark-grey: darken(@white, 70%);

@kepler-orange: #ff8c18;

.panel-primary {

border-color: @white;

& > .panel-heading {

color: @kepler-orange;

background-color: @dark-grey;

}

}Then manual application via className props:

<Panel> {/* Uses .panel styling from LESS */}

<PanelHeader />

<NextButton

bsClass='btn btn-default btn-circle' {/* Custom .btn-circle styling */}

/>

</Panel>It worked. But every style required both the LESS definition, and remembering to apply the right className. Manual all the way down.

Fast forward to 2018 though? The React ecosystem was maturing rapidly, and in a pretty different place. Design tokens and systematic theming were emerging as best practices. Semantic UI React was gaining popularity as a more modern alternative to Bootstrap, promising better integration with React's component model, and more sophisticated UI patterns out of the box.

2018-2021: The Semantic UI Era

April 25, 2018. We jumped ship.

- "bootstrap": "^3.3.7",

- "react-bootstrap": "^0.31.1",

+ "kip-semantic-ui-theme": "git+ssh://git@github.com/KeplerGroup/KIP-Semantic-UI-Theme.git#0.0.1",

+ "semantic-ui-react": "^0.79.1"You might notice something a bit different with the added dependencies here. We immediately created kip-semantic-ui-theme. Vanilla frameworks weren't enough; we needed customization.

This represented our first attempt at managed theming. Instead of manual LESS variables scattered throughout, we now had:

// webpack.config.js

entry: [

'kip-semantic-ui-theme/semantic/dist/semantic.css', // <-- Managed theme

path.join(PATHS.less, 'customMain.less') // <-- Custom overrides

]The hybrid approach: external theme package plus co-located overrides for specific needs:

// Custom overrides in customMain.less

.ui.segment.field-array-label {

box-shadow: none;

background-color: @light-grey;

}

.ui.menu .kip-services-nav-item {

padding: 0.92857143em 0em;

}Now we had systematic theming with escape hatches. Better than Bootstrap's manual approach, but still requiring us to remember specific CSS class targeting.

Again, at the time, Semantic UI React was exactly what we needed. Dropdowns with search built-in, modals that actually worked, and components that felt like they were designed for data-heavy applications.

With minimal design formalization at Kepler at the time (we had just four colors and basic typography, more outlined here) most of Semantic UI's out-of-the-box styling was more than sufficient. Function over form was our motto, and Semantic UI delivered. For three years, we were happy.

But also, here's what the git history of a few of our most active frontend repositories reveal: The Semantic UI era at Kepler didn't just last nearly three years, it was also more sophisticated than a simple linear progression.

Starting in July 2018, parallel to our main application development, we began building kip-react-components as a stand-alone library to house a dedicated application infrastructure layer. While our main applications used Semantic UI directly for basic components, kip-react-components focused on the complex orchestration that every business application needs: authentication, navigation, layout systems, and error handling.

Simply put, as we built more tools, we were also getting smarter about not rebuilding the same stuff over and over. By early 2020, this approach had proven so useful that all of main applications adopted it wholesale.

This continued separation of the implementation of app infrastructure and the apps themselves speaks to an interesting insight: application infrastructure and UI components can sometimes follow very different rules, and for good reason.

The Aurora Ambition, And Where It Fell Short

In early 2020, a refresh of Kepler's branding proved to be the opportune moment for us to build a fully spec'd out design system. I helped lead the charge on this, the process of which is outlined in this blog post I wrote a few years ago. This marked the beginning of us changing our mindset about function over form, and treating our design system as "a product in and of itself."

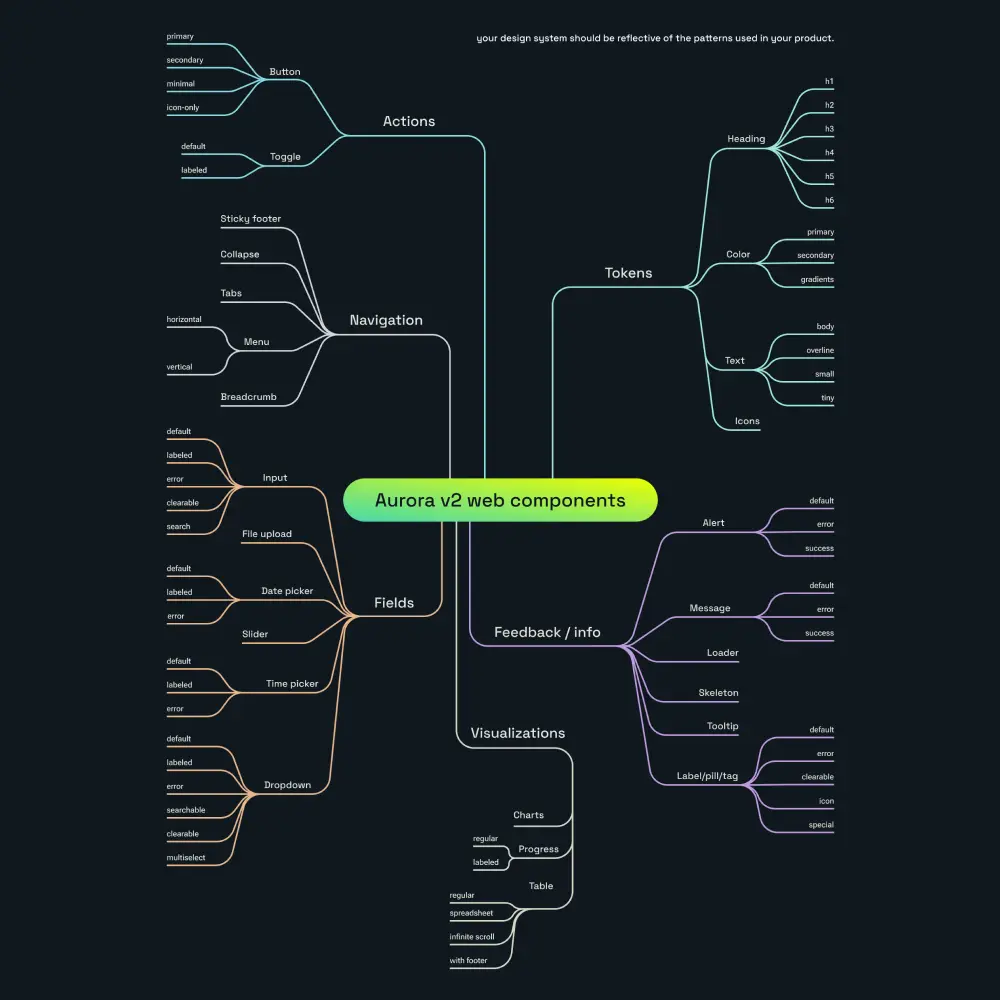

The vision was ambitious:

- Unified design language across all products

- Design tokens for systematic theming

- Advanced data visualization components

- Animation system using react-spring

By September 2020, we had it all:

{

"@kip-ui/react": "^0.6.2-alpha.2",

"emotion": "^10.0.23",

"jexcel": "4.2.0",

"react-responsive": "^8.0.1",

"react-spring": "^8.0.27"

}On paper, it seemed solid. Aurora had a robust toolkit: CSS-in-JS, a spreadsheet component, responsive utilities, animation libraries. It delivered big wins in consistency, accessibility, and developer experience.

But here's what that sophistication actually looked like. Systematic design tokens:

// @aurora/ui-constants

@kepler-sun-glare-400: #edff00;

@kepler-atmosphere-400: #2ad2c9;

@kepler-red-400: #ff6b6b;

@kepler-cosmos-700: #1a1a2e;

// ... 32+ systematic design tokensCSS-in-JS components consuming those tokens:

import { css } from 'emotion'

import { KEPLER_RED_400, KEPLER_PURE_WHITE } from '@aurora/ui-constants'

const errorIcon = css`

stroke: ${KEPLER_PURE_WHITE};

fill: ${KEPLER_RED_400};

width: 1.25em;

height: 1.25em;

`All while still built on Semantic UI foundations, with comprehensive theme overrides applying Aurora tokens to every Semantic UI color variable.

But under the hood, complexity was piling up, and the breaking points usually came with the smallest of updates.

Let's play out a scenario. Say you wanted to refactor a simple button variant, maybe your product manager asked you to change the padding and border radius. This should be a fairly quick update to implement. Instead, it looked like this:

- Update

@aurora/ui-themewith new styles. - Update

@aurora/ui-reactwith component changes. - Version bump both packages to a pre-release (alpha) for testing.

- Update and QA all consuming applications.

- Version bump both packages to a patch release.

- Update and QA all consuming applications again.

- Merge all PRs.

What could have been an hour’s work often stretched to a week or more, especially when QA timing hinged on product manager availability. It was a clear signal we needed to rethink our approach.

January 2024: Rethinking Aurora With A Committee

Fast forward to the rebrand announcement in January 2024. With multiple engineers now working on Aurora components, many of whom were not at Kepler durig the original 2020 redesign, we decided to take a moment to pause and gather wide input. To make a thoughtful, well-rounded decision, we formed a committee. After all, choosing the frontend stack that would shape our work for the next few years deserves more than a snap Slack poll.

Our first order of business: audit the components we use across all our apps, a sprawling collection built over 8 years. Each team member dove into the apps they knew, flagging frequently used components, recurring patterns, and features we were missing. Spoiler alert: there were plenty of both.

What emerged was clear. Tables, modals, and searchable dropdowns formed the backbone. Inline errors and contextual help (already showing up in some newer apps that we'd designed) stood out as patterns worth standardizing. Better loaders and skeletons surfaced as priorities, improving perceived performance and reducing those annoying layout shifts.

For some engineers, the audit doubled as an onboarding crash course into parts of the system they hadn’t touched before (while perhaps sparking a new appreciation for just how many dropdowns one company can use).

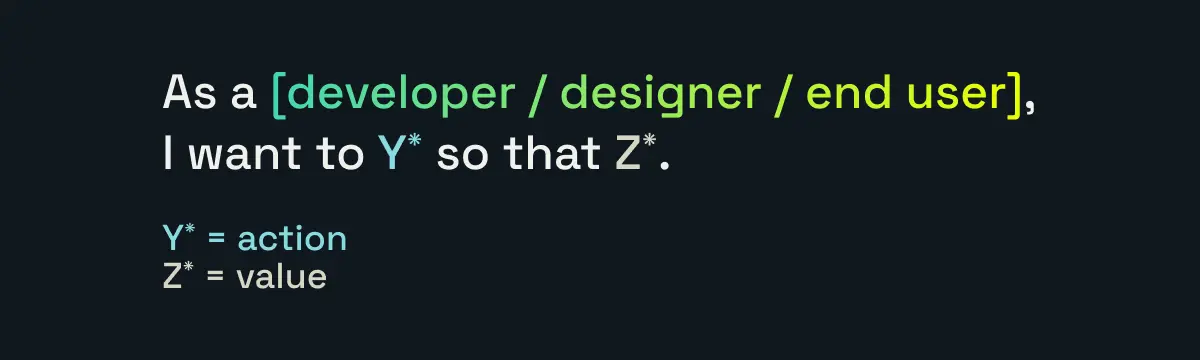

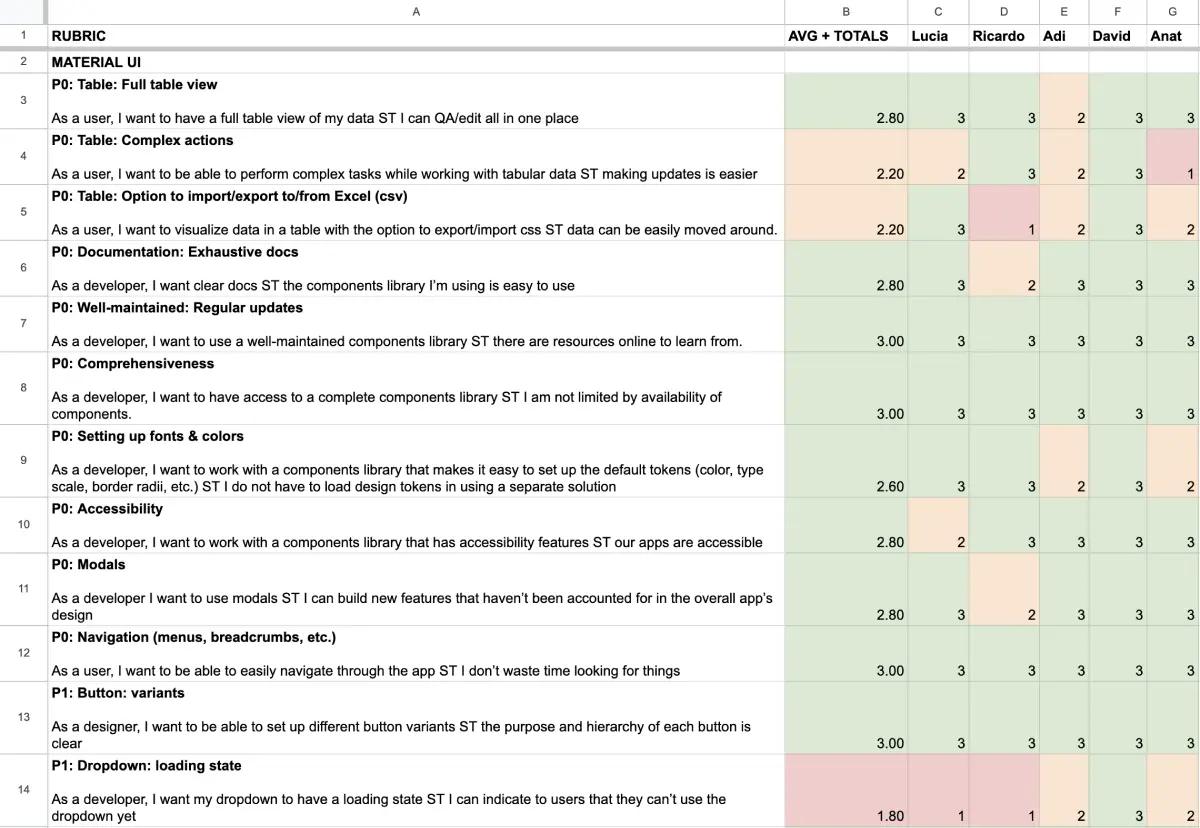

With the audit fresh in our minds, we needed a structured way to evaluate each library based on what truly mattered. This led to us building a rubric that provided a simple framework to guide our decision-making.

We grouped features into three buckets:

-

Essential: The non-negotiables. Tables that handle big datasets without breaking. Modals that support complex forms. Dropdowns with search.

-

Important: These weren’t dealbreakers, but they mattered. Inline validation that actually helps users, loaders that prevent annoying layout shifts, and TypeScript support that just works.

-

Nice-to-have: The cherry on top. Animation helpers for polish, advanced data visualization, and if we were lucky, a spreadsheet component.

To keep it grounded, we framed these as user stories from developers, designers, and end users. Ideally, we weren't just evaluating for features, but grounding our evaluation in real needs across a spectrum of users.

Then came the survey. Committee members rated each library using Likert scales and shared honest feedback. This balance of numbers and nuance helped us see strengths and weaknesses clearly.

Mantine and Material UI emerged as strong contenders, and we eventually decided to pick Mantine. Mantine was essentially the library that was good enough everywhere, and excellent where it counted.

18 Months Later, The Honest Assessment

Today, we've fully migrated two complex applications to use our Mantine-based nx monorepo system, and built one from scratch as well.

The wins so far have been real: we built a Pacing tool entirely with Mantine in half the time Aurora would have taken. Build Manager, the app that started it all, the app that used react-bootstrap all those years ago, has now been migrated from Semantic UI to Mantine, with a simplified design and a whole lot easier to maintain.

And what frankly came as a bit of a surprise to me, Kip's overall UI has been leveled up thanks to components we didn't even know we could have used -- number inputs, loading overlays, floating indicators, and much more.

Looking back, there's a clear pattern in our styling evolution. We went from Bootstrap's manual LESS variables to Semantic UI's managed themes to Aurora's systematic design tokens and strategic CSS-in-JS. Each step added sophistication, but with it, some amount of maintenance overhead.

Mantine brought us full circle to something that feels almost like inline styling again, but intelligent. Here's what that actually looks like:

Our KipButton implementation:

// libs/components/src/components/KipButton/index.tsx

import { Button as MantineButton } from '@mantine/core'

const _KipButton = ({ variant = 'primary', size = 'md', ...restProps }) => (

<MantineButton

classNames={styles} // CSS modules for brand-specific styling

mod={{ label: hasLabel, variant }} // Mantine's mod system

size={size} // Built-in sizing

{...restProps} // All Mantine props available

/>

)The CSS modules approach:

/* KipButton.module.css */

.root {

/* Brand-specific overrides using theme tokens */

background-color: var(--aurora-cosmos-700);

}Theme and css variable configuration with preserved Aurora colors:

// libs/components/src/theme.ts

export const theme: MantineThemeOverride = createTheme({

other: {

sunGlare400: '#edff00', // Aurora design tokens preserved

atmosphere400: '#2ad2c9', // but now managed by Mantine

cosmos700: '#101820'

// ... 30+ design tokens now as theme variables

}

})

export const resolver: CSSVariablesResolver = (theme) => ({

variables: {

'--aurora-body-font-size': theme.other.body.fontSize,

'--aurora-body-font-weight': theme.other.body.fontWeight,

// ... 13+ other font styles available as css variables

'--aurora-sun-glare-400': theme.other.sunGlare400,

'--aurora-atmosphere-400': theme.other.atmosphere400,

'--aurora-cosmos-700': theme.other.cosmos700

// ... 30+ colors available as css variables

}

})It's a hybrid approach: component props like size="md" and variant="primary" for behavior, CSS modules for brand-specific styling, all backed by a mature theming system we don't have to maintain. The return to simplicity, informed by everything we learned building the complex stuff.

Conclusion

Eight years ago, we picked Bootstrap because it was obvious. Today, we're using Mantine for the same reason.

The frameworks changed. The underlying truth didn't: the best technical decisions aren't about finding perfect solutions. They're about matching tools to problems at the right time. Ultimately, we learned to separate what we're uniquely good at (building ad tech tools) from what the community has already solved well.

(And if you're reading this in 2032 wondering why we moved on from Mantine, check the git history. I'm sure we had our reasons.)

P.S: if you're interested, we've open-sourced our evaluation rubric. You'll find our Likert scales, component audits, and the actual survey results here.